When Gérald Marie, 75, presided as the European president of Elite Model Management (1980-2000), he single handedly chose which woman would get a multi-million dollar contract, and be splashed across every magazine cover around the world into super stardom.

Fifty years on, former Elite supermodels gathered during Fashion Week at a Judicial Tribunal in Paris to accuse Marie of sexual harassment, assault and rape. Due to a French statute of limitation, the sexual assault and rape of an adult cannot be prosecuted in France after 20 years.

“Enough is enough,” said Carla Bruni, one of the most famous models of the ’90s and the former First Lady of France. I stand with the survivors of Gérald Marie as they come to Paris to testify against their abuser.” She's just one of many high-profile global leaders now calling for new labor regulations to address sexual harassment in the workplace.

Life Magazine called them “million-dollar faces” when Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Naomi Campbell and Cindy Crawford were all commanding million-dollar contracts. They appeared together in the now iconic Vauxhall Corsa commercial for $8.5 million, the single most expensive advertising shoot of all time.

Vogue’s editor Anna Wintour said, “those girls were icons of their time,” but Elite’s Gérald Marie was the star maker. Their roads to fame, fortune, or incomprehensible demoralization all began at Elite.

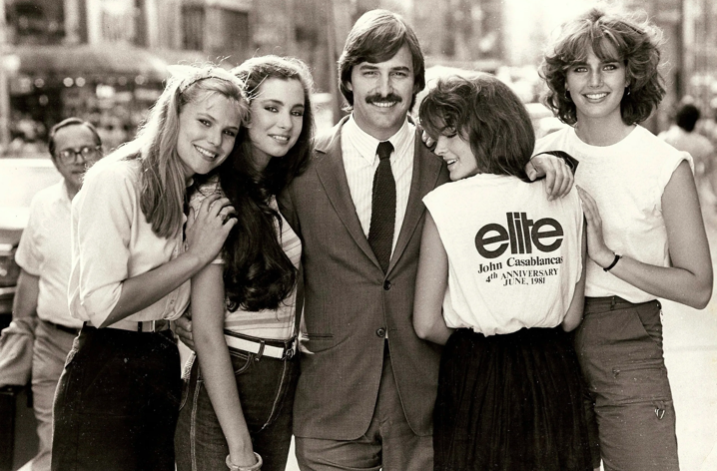

Elite Founder John Casablancas 1990

While the Civil Rights Acts of 1875, 1957 and 1960 enshrined the civil rights of African Americans into the US Constitution, each and all were ultimately varnished by amendments and invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court. However, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a game changer.

It prohibited discrimination based on race, color, national origin, religion and sex. Women, for the first time in American history, could not be discriminated upon based on their sex, and stood shoulder to shoulder with men as a protected class within the US labor force.

Teaching a class called "Women at Work,” Lin Farley, an instructor at Cornell University, noticed a recurring theme. Women in the U.S. workforce in 1974 were routinely terminated after reporting feeling harassed and intimated by men. She coined the phrase “sexual harassment,” and describes the dynamic in a 1975 testimony before the New York City Human Rights Commission.

As complaints began trickling through the courts, litigators had neither a standard working definition of sexual harassment, nor any case law or precedent with which to prosecute it. Moreover, forced arbitration clauses, hidden deep within the employee’s contracts, ensured that any internal disputes be mediated by the company.

Working Women United — Farley’s woman’s organization dedicated to combating sexual harassment in the workplace — foresaw the confusion and lobbied the U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission to conjoin sex discrimination to sexual harassment as a federally protected constitutional right. Title VII later expanded woman’s right to sue and collect punitive and compensatory damages for sex discrimination and sexual harassment.

Barns v. Train (1974) is commonly viewed as the first sexual harassment case in the United States. Opening arguments were heard exactly 10 years to the day following U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law.

French and American companies have fought long and hard to hijack their employees and customer’s right to sue them. Not only do forced arbitration agreements bar individuals from filing their own court claim, they often forbid litigants from pursuing group claims, too.

Since commercial arbitration is based upon the law of treaties, an agreement between the parties to submit their dispute to arbitration is a legally binding contract. All arbitral decisions are considered to be final and binding, thus bypassing the criminal justice system and putting the power to resolve a dispute squarely within the company’s discretion.

Nearly 54% of nonunion, private-sector employers have mandatory arbitration procedures, representing 60 million workers, according to a 2020 Economic Policy Institute study. Among companies with 1,000 or more employees, 65% have mandatory arbitration policies which never see a courtroom. While prospective employees cannot be coerced into signing an arbitration clause, neither will they be hired without signing an employee contract.

A recent United States Supreme Court ruling — EEOC v. Waffle House, Inc — held that forced arbitration agreements cannot prevent the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) from pursuing victim-specific relief in litigation on behalf of an employee who files a charge of discrimination.

In 2022, the U.S. Congress passed the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act. “For too long, enforcement of pre-dispute mandatory arbitration agreements has served as a potential barrier to justice for individuals who have suffered assault or harassment at work,” says the EEOC Chair Charlotte Burrows. “While private parties are bound by arbitration agreements, the EEOC is not. Private parties can continue to file charges of discrimination for the EEOC to investigate and litigate in perpetuity.”

While its difficult to prosecute sexual harassment in France — due to expiring statutes of limitation, and forced arbitration agreements — the United States, who led the global discussion on civil rights in 1964, now ensures that all disputes of sexual harassment be put on the scales of mercy and justice without prejudice. When Ebba Karlsson left Sweden in 1990, the stars aligned to lead her to sign in Paris.

Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell

“When I arrived at his office,” she began, of her first interview with Gérald Marie, “the first thing he did was lower the blinds. There was a full-length window between his office and the agency,” she explains, of the Elite modeling empire in Paris.

As Marie took the newly signed and papered 20-year old through the magnificent portfolios of supermodels the agency represents, he asked, “savez-vous comment ils ont réussi?” Do you know how they became successful?

He stands from behind the desk, a titan of the modeling industry, who, at just 39 years old, has the power to bend the shape of a person’s soul. He rises from behind his desk, turns the corner of propriety, straddles the proverbial casting couch, and assumes a seat next to the ingénue.

His fingers playfully fall on her knee, soon finding their way up her skirt, and to the islet of her innocence. Silent, she modulates her breathing whilst turning the plastic covered pages of a portfolio whose supermodels silently testify to the special skills and job requirements expected of Elite applicants.

How well she knew the Gamla stan; where a sudden unforgiving vortex of cold air can transform a glazing event into a picture perfect winter wonderland. Nordic cuisine, chic cocktail bars and luxury shopping lure tourists onto cobblestone streets, colorful 17th century buildings, and into medieval castles like the Kungliga slotten. Well-rehearsed productions of snow and ice-based games belie the paralysis of winter, and the wonder and resilience of Sweden.

In her memoir, “True Starlight: From Hiding in the Shadows to Being Stellar,” Karlsson dedicates the book to her younger self. A real account of sexual harassment and assault at the Elite Modeling Agency in Paris, Karlsson’s cautionary tale of celebrity culture and impressions offers an insightful playbook for acquiring authentic power in a modern world.

Her “Victorious Angels,” a global consortium of abuse survivors of Gérald Marie, spread their once clipped and broken wings and flew to Paris. Like the goddess Juno, who flew to Rome to warn a republic of the Gaul's unwelcome approach, she and they appear to empower all women everywhere in Apple TV+ “The Super Models.”

Archives